I was wondering what the largest gap is between reuses of the name of an English monarch (including British monarchs after the merger). The situation becomes more complex if you also look at Scottish monarchs (because sometimes they overlap and sometimes they don’t), so I have not looked at them. It’s not that I think Scottish monarchs are any less worthy, it’s just that the English ones were the ones I was thinking about, being the ones I am familiar with.

Here are the reused names listed alphabetically (I’ve decided semi-arbitrarily that Æ comes before C). To represent the end of one reign I’ve used the letter d (for “death”, though it wasn’t always), and s for the start of the next reign with that name.

Æthelred

d. 871, the Unready s. 978 = 107 years.

Charles

I d. 1649, II s. 1660 = 11 years.

II d. 1685, III s. >2010 > 325 years. [This is the current Prince of Wales – I was just curious, haha.]

Edgar

the Peaceful d. 975, the Ætheling s. 1066 = 91 years.

Edmund

the Magnificent d. 946, Ironside s. 1016 = 60 years.

Edward

the Elder d. 924, the Martyr s. 975 = 51 years.

the Martyr d. 978, the Confessor s. 1042 = 64 years.

the Confessor d. 1066, I s. 1272 = 206 years.

I d. 1307, II s. 1307 = 0 years.

II d. 1327, III s. 1327 = 0 years.

III d. 1377, IV s. 1461 = 84 years.

IV d. 1470, V s. 1483 = 13 years.

V d. 1483, VI s. 1547 = 64 years.

VI d. 1553, VII s. 1901 = 348 years.

VII d. 1910, VIII s. 1936 = 26 years.

Elizabeth

I d. 1603, II s. 1952 = 349 years.

George

I d. 1727, II s. 1727 = 0 years.

II d. 1760, III s. 1760 = 0 years.

III d. 1820, IV s. 1820 = 0 years.

IV d. 1830, V s. 1910 = 80 years.

V d. 1936, VI s. 1936 (though not immediately succeeding) = 326 days = 0 years.

Harold

Harefoot d. 1040, Godwinson s. 1066 = 26 years.

Henry

I d. 1135, II s. 1154 = 19 years.

II d. 1189, III s. 1216 = 27 years.

III d. 1272, IV s. 1399 = 127 years.

IV d. 1413, V s. 1413 = 0 years.

V d. 1422, VI s. 1422 = 0 years.

VI d. 1471, VII s. 1485 = 14 years.

VII d. 1509, VIII s. 1509 = 0 years.

James

I d. 1625, II s. 1685 = 60 years.

Mary

I d. 1558, II s. 1689 = 131 years.

Richard

I d. 1199, II s. 1377 = 78 years.

II d. 1399, III s. 1483 = 84 years.

III d. 1485, Cromwell s. 1658 = 173 years.

William

I d. 1087, II s. 1087 = 0 years.

II d. 1100, III s. 1689 = 589 years.

III d. 1702, IV s. 1830 = 128 years.

From this list we can see that the biggest gap between reuses is with William, with 589 years between the end of William II and the start of William III. Second is Elizabeth, with 349 years, then Edward with 348 years between VI and VII.

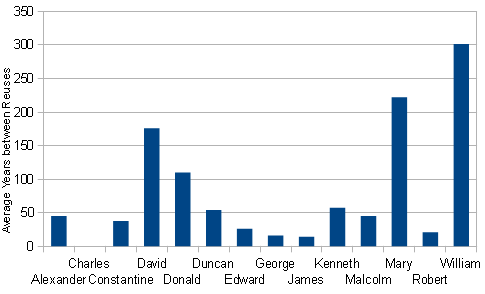

Here is a graph of the average gap between reuse for each name. It should be noted the data here is only so informative, and is a bit misleading – even though Edward is third in terms of maxima, it is seventh by average. Similarly, there is an 80 year gap between Georges IV and V, but the other four gaps of 0 years drag the average down to 16.

Also interesting is that the name with the biggest time-span between first and last uses is Edward: Edward the Elder started his reign in 899, and Edward VIII ended his in 1936, spanning 1037 years. Granted, this has something to do with the number of times the name was used, but Henry and George are the next most common, while William is in fact second in terms of the amount of time between first and last uses (with 771 years, compared to 447 for Henry and 238 for George).